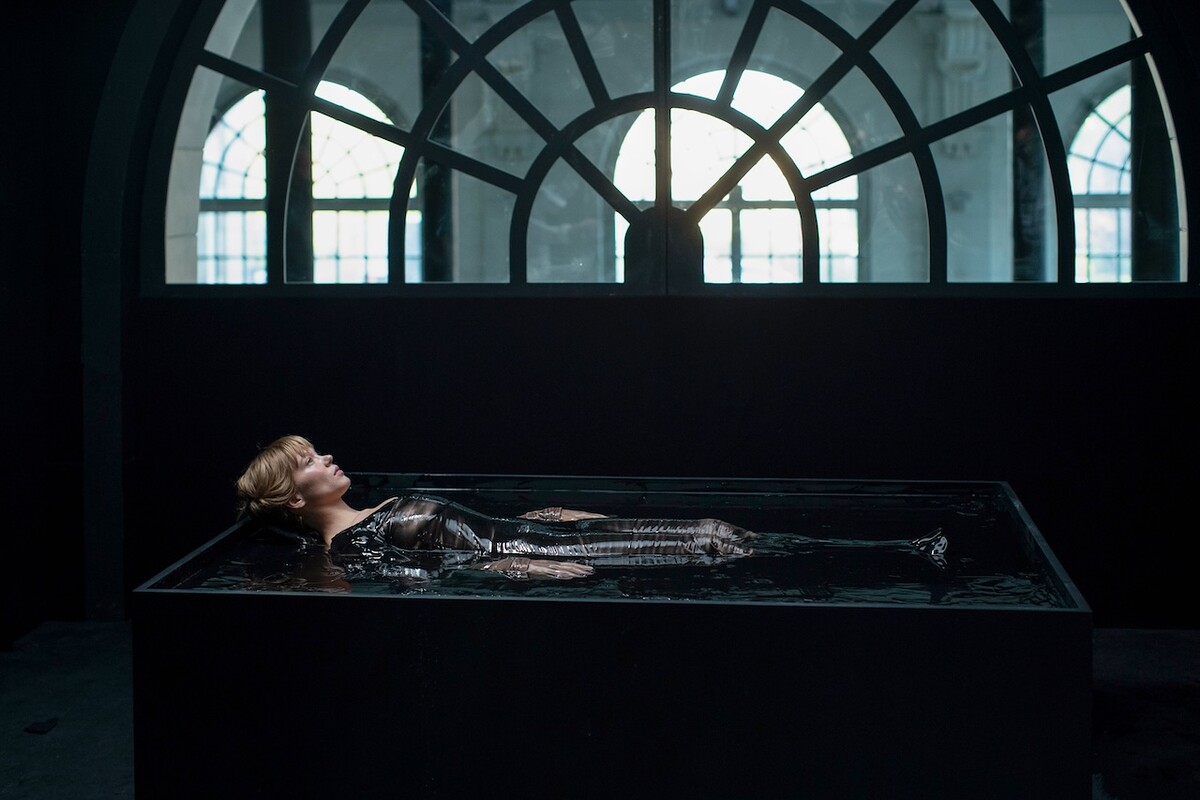

Still from Bertrand Bonello, The Beast (2023).

In the prologue to The Beast, Bertrand Bonello’s latest film, we see Gabrielle, an actress played by Léa Seydoux, performing a green-screen scene in a horror movie: in an empty room she screams, moves around, picks up a knife, and imagines herself confronting an unidentified beast. But behind her, there is no set design, only an abstract technological apparatus at the service of a subsequent digital reinscription. And in fact the scene morphs into a digital glitch before finally disappearing from the screen and thus beginning the film. It would be enough to look at outtakes from recent superhero movies or disaster films to see how much of mainstream cinema has very similarly completely abandoned the passivizing dimension of the photographic—that dimension which fascinated Bazin and Deleuze for its ability to castrate artistic authorship and allow a new kind of machinic, unconscious, and anguished visuality to emerge. By contrast, today’s cinema—precisely because of its scriptural and digital vocation—is increasingly close to animation. What is left of the visual unconscious of the photographic? Of that dimension of visuality that emerged when the camera started to look at the world independently of the mediation of the artist, dethroning the aristocratic artisan, with his craft and savoir faire, in favor of the petit-bourgeois operator of a machine?

It would seem a paradox, but this is what Bonello captures most convincingly in the part of the film that takes place in 2044, in a world that closely resembles our own but is dominated by artificial intelligence. It is a world that suppresses the heterogeneous and the unconscious, a world where humans are not only reduced to appendages of machines (Seydoux’s job is to check the temperature of a data plate, something that could seemingly be done by rudimentary machines even today) but are also reprogrammed to suppress any disturbing emotions. What we see is paradoxically a much more “human” world, though this humanity is without fear or anxiety, and thus without the “inhumanity” of the unconscious and the blind spots of subjectivity: AI is in fact represented by Bonello as a world of absolute visibility. The woman played by Seydoux undergoes an operation to reprogram her entire DNA and erase all fear and past trauma. It is only because of a 0.7 percent margin of error in the machine that the protagonist’s body involuntarily resists the operation.

“We should always read stories from the end,” Bonello tell us through the film’s male protagonist, played by George MacKay. From this unpredictable side effect in 2044, the film unravels through two other past time lines, almost as if they were the return of the repressed: London in 1910 and Los Angeles in 2014, where two protagonists who look identical to the two protagonists from 2044 meet again, often reciting similar lines and behaving in similar ways. The effect is that of a pulverized history, which, as in a mirror shattered into a thousand pieces, is made up of scattered chunks of time. (It is no coincidence that one of the clubs in 2014 Los Angeles is called Fractal.) This atmosphere is rendered even more opaque by the profusion of digital screens, closed-circuit cameras, fictions, and out-of-control simulacra (from 1910s dolls to modern-day robots), as well as by future prefigurations (psychics, like in Bonello’s Zombi Child) and bits of nostalgia, like the discotheques of the future where one dresses and dances as if it was 1963 or 1980.

It is within this fragmentary structure that the film’s main narrative theme takes shape, repeating itself in each temporal stanza. This theme derives from the novella “The Beast in the Jungle” by Henry James. In this 1903 work, James—similar to Bonello in The Beast—pushes the limits of an analytic overtreatment of subjective interiority through a narrator who is more a witness than a hero of the story.

“The Beast in the Jungle” (which corresponds in broad strokes to the 1910 timeline of the film) tells the story of John Marcher and May Bartram, who run into each other at a party in London. A decade earlier they met while on a vacation in Naples, with the complicity of common acquaintances whom they now barely remember. During a walk near Sorrento, John confided a secret to May, which ten years later in London they manage to recall and bring into focus. This secret is enough to build a strange complicity between them—one with no sentimental dimension—that will accompany the two protagonists throughout their lives, until death. “The Beast in the Jungle” is characterized by what Edmund Wilson calls “the ambiguity of Henry James”: “[This ambiguity] was eventually to pass all bounds in those scenes in his later novels … in which he compels his characters to carry on long conversations with each of the interlocutors always mistaking the other’s meaning and neither ever yielding to the impulse to say one of the obvious things that would clear the situation up.”1 It is these seemingly pointless long conversations that will bring the later Henry James closer to what will be called the “anti-novel,” and that make up almost the entirety of the dialogue in “The Beast in the Jungle.”2

Bonello extracts from this story-without-a-story (literally nothing happens in James’s novella) a melodramatic structure, i.e., the idea of telling a story that centers on the obstacle that makes a couple’s love impossible (but at the same time elevates it to an absolute idea). The “beast” in James’s story is the obstacle that will ultimately prevent the couple from becoming one: a kind of looming threat that makes John a character eternally “in a waiting room,” a quintessential obsessional neurotic unable to turn the time of waiting into a moment of decision. And yet the brilliant coup de théâtre of the conclusion of the novella—a truly dialectical twist—is when John realizes that the event he was waiting for was right there in front of his eyes: it was the love of May, who waits for him her whole life, sacrificing her own happiness for him. “The beast” thus transforms from an external threat into an internal one: it is the failure to catch the kairòs of subjective choice in the moment when it appears. James’s novella is ultimately about the inability, so typical of male obsessional neurotics, to make a decision and thus break the repetition of time.

The structure of time today has become increasingly horizontal: we experience segments of time that come and go in a never-ending cycle of permutations and substitutions—an eternal cycle of repression and the return of the repressed. Time seems incapable of becoming vertical and transformative. In Bonello’s film, the love story of Gabrielle and Louis is destined to repeat itself as an eternally missed encounter, prophesied by a digital psychic who in fact correctly predicts that their sexual encounter will only take place in dreams (i.e., in fantasies).

It is interesting that Bonello, who has always been fascinated by passages à l’acte (like in his film Nocturama, which is a story of a political acting-out that flirts with the imaginary of the Invisible Committee) and stories of para-psychotic subjective destitution (like in Zombie Child), here makes a quintessentially neurotic film based on impossibility and frustration, and the inability to perform a sexual act. The Beast is indeed a film that shows the anxiety that dwells at the core of sexuality, exemplified in the section on an LA incel, based on the real-life Elliot Rodger. Bonello translates this anxiety into a dense series of visual motifs that act as obstacles to sexuality, from digital screens, to a devilish pigeon, to dolls, to digital pop-ups. However, the greatest obstacle to the sexual encounter between Gabrielle and Louis will be the ever-looming threat of catastrophe, which unlike James’s novella is here also social and political: the Paris flood of 1910, which will eventually drown the couple in a fire of dolls and glass eyes (a paradoxical coexistence of fire and drowning, which constitutes one of the most remarkable visuals of the film), but also the Los Angeles earthquake of 2014, which allegorizes a world of ubiquitous narcissism (e.g., social networks, but also the fashion world, embodied here by Dasha Nekrasova, who essentially plays herself) and incel misogyny. And yet, as in all stories of neuroses and in all true melodrama, the impossible is also and always a condition of possibility for the love encounter; terror is also and always a principle of eroticization; anxiety is also and always a means to give form to subjectivity. The Los Angeles slasher movie that occupies the center of the film and can only end in a literal pool of blood maintains the simulacrum of a possible encounter and mutual understanding between Gabrielle and Louis. But the real catastrophe, Bonello tells us, is the absence of catastrophe.

It is a world where AI has the “human, all too human” face of actress Guslagie Malanda, the final incarnation of the motif of the dolls that traverse the entire film, which become more human from 1910 to 2044. This Malanda-faced AI is among the last true inhabitants of an oxygen-deprived earth, able to walk around without a mask. A world where fear and “the beast” have been hygienized, and can no longer pose any threat. Is Seydoux’s final cry, then, a sign of resistance? A last gasp of an inhuman, and therefore fully human, anxiety? Perhaps. But Bonello’s true stroke of genius comes at the very end of the film, almost a finale after the finale: instead of the ending credits, there is a QR code. So at the very end, to see the list of people who worked on the film, the fourth wall crumbles and we have in front of us what had been implicitly prophesied during the previous two-and-a-half hours of the film: an audience of smartphones pointing at the movie screen.

Wilson, “The Ambiguity of Henry James,” in The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects (John Lehmann, 1948), 100.

This point has been developed by Alberto Rollo in “La Bestia di Lamb House,” his introduction to the Italian version of Henry James, La tigre nella giungla (Il Saggiatore, 2022).